I trusted the lab reports. For three years, every oil analysis came back “normal wear levels”—no red flags, no trending metals, nothing to worry about. Yet when I finally looked inside with a borescope, I discovered both engines had spalling camshafts. The very components doing the worst damage had somehow eluded detection by every oil lab I sent a sample to.

Oil analysis is a useful tool—but it’s not a guarantee. It can miss the beast hiding in the details. What a borescope reveals is often what your lab results won’t.

If you’re relying solely on oil reports to monitor engine health, this post is for you. Before you trust “normal” to mean “safe,” read what went wrong for me—and what might be going wrong in your engine, too.

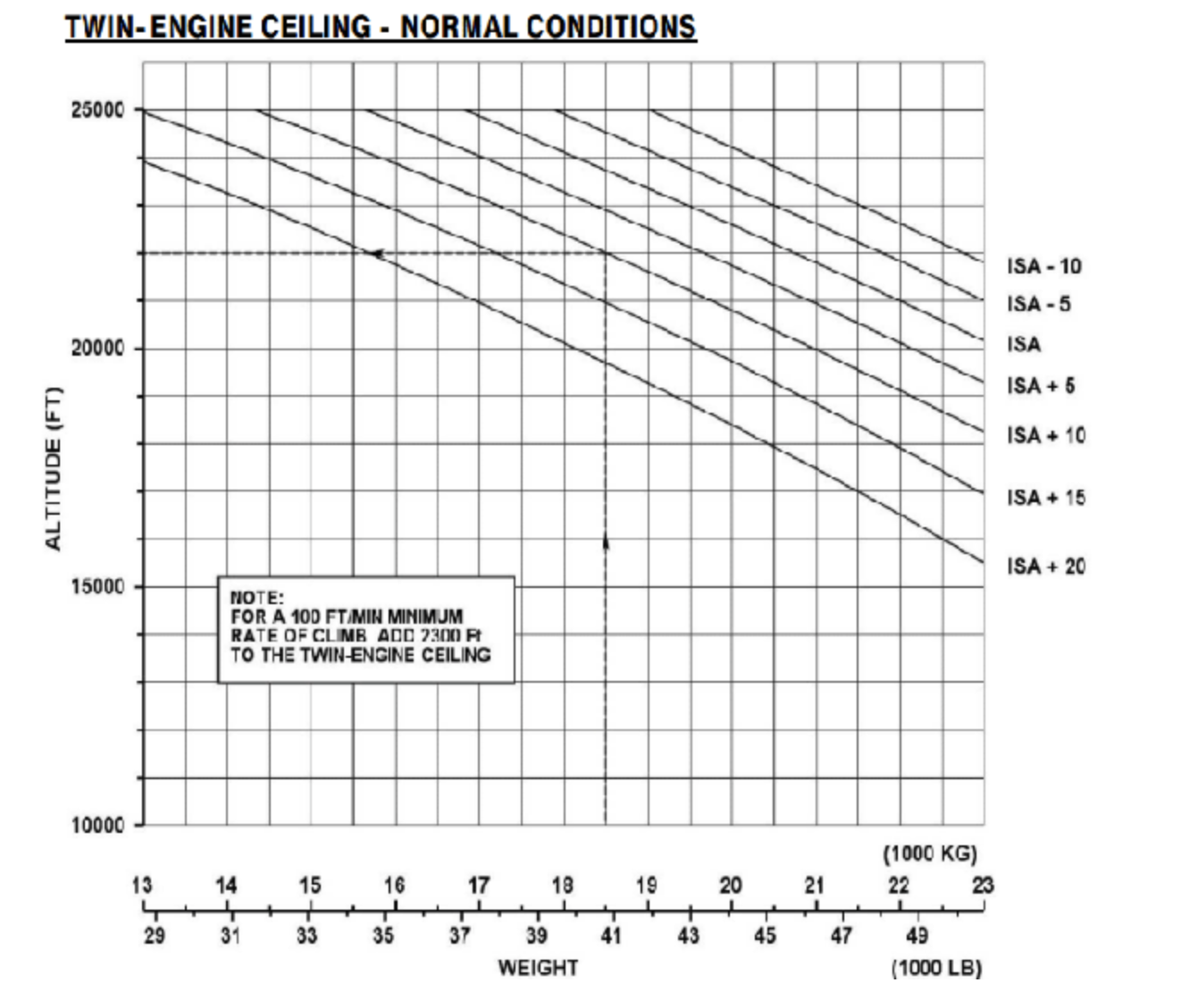

Engine failures significantly impact aircraft performance, reducing power by 50% and performance by over 80%. Pilots must consider factors like runway length, obstacle clearance, and performance ceilings during takeoff and en-route operations. Understanding declared distances (TORA, TODA, ASDA, LDA) and performance ceilings (service, absolute, single-engine) is crucial for safe decision-making in case of an engine failure.

Multi-engine aerodynamics involve understanding Vmc, the critical engine, and four aerodynamic factors (PAST) affecting controllability. Vmc varies based on conditions (SMACFUMO), with factors like density altitude, power setting, and propeller configuration influencing it. Understanding these factors is crucial for safe operation on one engine.