Oil analysis has become one of the most common tools aircraft owners use to “keep an eye” on engine health. So for years, I thought I was doing everything right when it came to engine monitoring. Every oil change, I’d pull a sample, send it off to the lab, and wait for the report to come back. A few days later, I’d get an email with a neatly formatted report indicating a clean bill of health containing reassuring phrases like “Normal wear metals. No action required.”

That went on for three years.

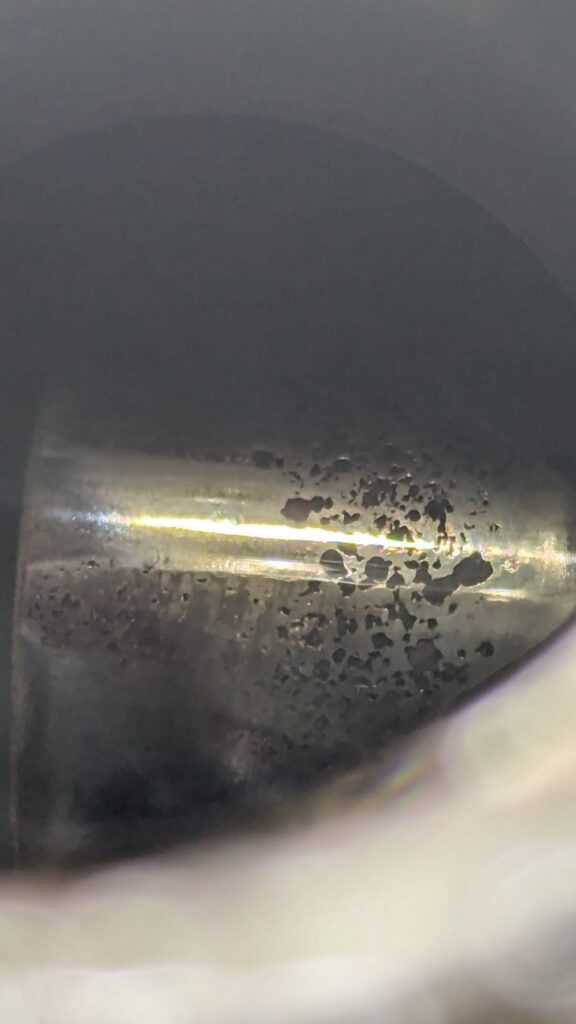

Then one annual, during a borescope, my shop reported that some of the cylinders had reduced valve lift. Unfortunately, that probably only meant one thing — flattened camshaft lobes. I had the shop pull some of the tappets on the valves that had reduced lift and indeed, I had spalling camshafts on both engines.

You read that right — both. And every single oil analysis report leading up to that point showed nothing unusual. Perfectly normal wear levels across the board.

That’s when I learned the hard way: oil analysis isn’t the end-all, be-all of engine diagnostics.

What Oil Analysis Does (and Doesn’t Do)

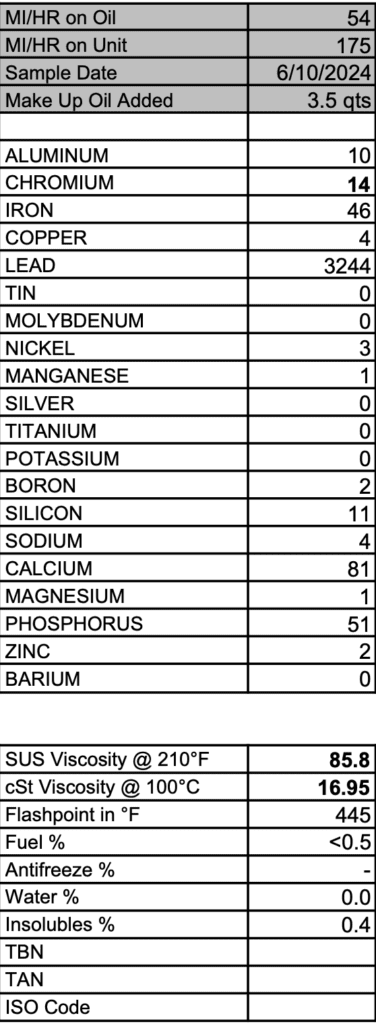

Oil analysis sounds scientific, and it is…to a point. The lab breaks down the oil sample and measures the concentration of metals like iron, aluminum, copper, and chromium. Each of those elements corresponds to a specific engine component, so theoretically, if something starts wearing excessively, you’ll see the numbers rise over time.

Oil analysis depends on two big variables:

- Particle size

- Particle distribution

When a camshaft, lifter, or bearing starts to spall, the wear process creates a wide range of particle size. Large flakes get caught in the filter or drain out during an oil change, meaning they might not ever make it into your sample bottle. On the other end, microscopic debris stays suspended and can be analyzed, but some of them may too small to significantly affect the lab’s readings. This means that some damage produces debris that’s just too large, too small or too localized to ever show up in measurable amounts.

Most oil analysis labs use spectrometry, which only measures particles below about 5–10 microns in size. Anything larger than that doesn’t get vaporized in the plasma torch and never shows up in the results.

So even though the lab data looks scientific and precise, it’s still an indirect sampling of a non-uniform system. The report you receive may still says “normal wear” — while your engine quietly tears itself apart. By the time you see a spike in metals, the damage is already done. Oil analysis is excellent for spotting trends, like a gradual increase in copper or silicon, but it’s not a real-time diagnostic tool. It can’t tell you if your exhaust valve is burning, your camshaft lobes are delaminating, or your cylinder walls are scoring. It just reports what happens to be floating around in the oil sample.

That’s exactly what happened to me.

Seeing Is Believing: The Case for the Borescope

After that experience, I completely changed how I think about engine health. The only way to really know what’s going on inside is to look inside.

A borescope gives you a direct view of the engine’s condition. You’re not guessing based on numbers — you’re actually seeing what’s happening in your cylinders.

A good borescope inspection can reveal things no oil report ever will:

- Burnt or asymmetrical exhaust valves that may look fine in compression tests.

- Valve guide wear and lead fouling that could cause poor sealing or sticky valves.

- Cylinder wall scoring or corrosion patterns that indicate ring or lubrication issues.

- Abnormal combustion signatures such as hot spots, detonation, or excessive deposits.

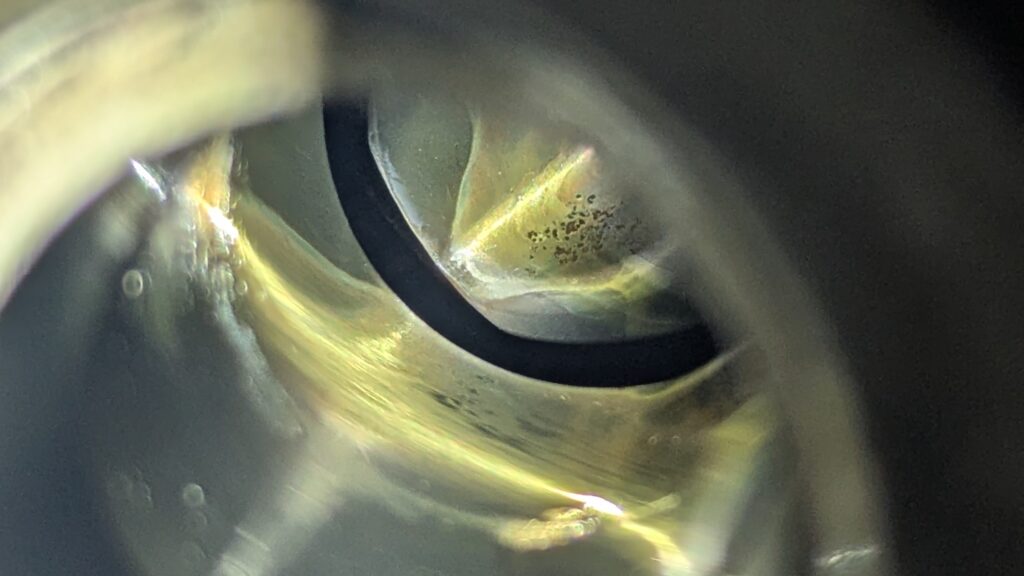

With a bit more work, at least on Continental engines, you can even use the borescope to look directly at the cam lobes. This gives you direct reassurance that everything is OK, or potential to catch issues before they become catastrophic.

When done consistently, a borescope turns into a visual history of your engine’s life. You start to recognize what normal looks like for your setup, and that’s when you can really spot the subtle changes that matter.

Oil Analysis Still Matters — Just Not Alone

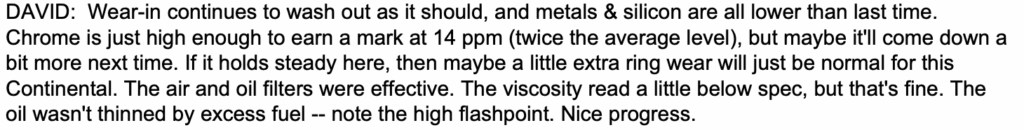

To be clear, I’m not saying to toss your oil analysis kit in the trash. It’s still a useful tool and still has a place in maintenance, especially when used to track trends over time. If you suddenly see a spike in a specific metal, or contamination from silicon or coolant, that’s valuable information. However, on it’s own, it is insufficient.

The full picture of engine health comes from using:

- Oil analysis for wear trends and contamination monitoring

- Borescope inspections for real-time, visual condition assessments

- Oil filter inspections for capturing large particles missed by the lab

When you use all three together, you’re no longer relying on a single data point — you’re building a comprehensive view of what’s happening inside that engine.

The Lesson Learned

After discovering those spalling camshafts, I stopped viewing oil analysis as an “engine health guarantee.” It’s not. It’s a helpful indicator, but not a crystal ball.

The borescope, though? That’s the truth-teller.

Every oil change, every annual, I take a look. It’s not necessarily quick, but it is inexpensive (if you do it yourself), and it’s the best insurance policy I know of.

Engines rarely fail without warning. The signs are there but you have to be willing to look.

Comments are closed